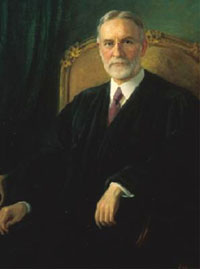

Who was George Sutherland? Some remember him as a Michigan-trained justice of the United States Supreme Court, but he was more than that.

Seventy years ago this month — May 27, 1935 — Sutherland led the charge in striking down what may have been the greatest legislative roadblock ever put in the path of free enterprise in America: the National Recovery Act. Sutherland’s victory in declaring the NRA unconstitutional returned competition to American business and lowered prices for consumers.

Sutherland was a quiet, unlikely hero. Born in England in 1862, he and his parents migrated to Utah in the 1860s, and made their living from mining. Young Sutherland showed strong aptitude, and after schooling in Utah he went to the University of Michigan law school. In Ann Arbor, he studied under Thomas Cooley, whose landmark bookConstitutional Limitations educated generations of students in the virtues of limited government.

Sutherland learned his lessons well and returned to Utah committed to supporting free enterprise and natural rights, which stressed the individual worth of each person and the importance of providing constitutional protection to everyone. He entered politics in Utah — a protestant in a Mormon state — and won election first to the state legislature, then to the U.S. House of Representatives, and finally to the U. S. Senate.

In 1922, President Harding appointed Sutherland to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Sutherland became a jealous protector of individual liberty. One of his first cases, for example, was Adkins v. Lyons in which Sutherland supported a woman’s right to negotiate a wage contract for herself — without state regulation. In a later case, New Ice Company v. Liebmann, Sutherland wrote the majority opinion that struck down an Oklahoma law that virtually prohibited anyone from entering the ice business to compete with the monopolistic New State Ice Company.

As Sutherland was to discover, the New Ice case was the tip of an emerging iceberg in government regulation. The NRA, which was part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program, far surpassed the New State Ice Company in its threat to free enterprise. All major industries in the nation were invited to form cartels. They were urged to develop industry-wide codes that would regulate the prices charged for the products they made, wages paid, number of hours worked, and even the quality of products sold. These NRA rules would, in practice, be binding on all corporations in their industry, even those who opposed such interference.

Over 500 NRA codes emerged, which stifled American production through higher prices for goods and lack of innovation in industry. As monetary expert Benjamin Anderson observed, “NRA was not a revival measure. It was an anti-revival measure.” Indeed, it was a major reason the Great Depression worsened in 1933.

Finally, the Schechter brothers challenged the constitutionality of this law which forced so much of American business into a straitjacket. Their lawyers observed that the NRA was trying “to regulate human activities literally from the cradle to the grave and beyond.” For example, the tailors of America decided in their code to establish 40 cents as the minimum price that could be charged to press a pair of pants. When Jack Magid in New Jersey charged a customer only 35 cents, he was sent to jail for breaking the law.

In the Schechter Poultry Corporation v. U.S. case, Sutherland ruled against the NRA and for the rights of the Schechter brothers to sell chickens freely in the Jewish community of New York City. Justices Sutherland and James McReynolds were effective in their questioning — so effective that the audience frequently erupted in laughter as the government tried to explain why customers should not have been allowed to select the particular chickens they wished to purchase from the Schecters, but should have had them selected randomly instead.

So persuasive was Sutherland, and so bad was the NRA, that the Supreme Court voted unanimously that the law was unconstitutional. Three years later Sutherland retired from the court, leaving future generations to defend the Constitution. Seventy years after his landmark rebuke of the NRA we should remember him for his commitment to individual liberty and for temporarily halting the rise of big government.

#####

Burton Folsom, Jr. is professor of history at Hillsdale College and senior fellow in economic education at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Midland, Mich. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided that the author and the Center are properly cited.

Pastorius comment: Let us hope that, in Supreme Court Justice John Roberts, we have another Sutherland.

No comments:

Post a Comment