At the end of August 1965, at the height of the Indo-Pakistani War, Indian troops had captured and occupied the Haji Pir pass and other important strategic territory in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Operation Gibraltar — Pakistan’s mujahideen-powered attempt to infiltrate and overthrow the government of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir — had failed. Indian forces were better-equipped and supplied than their Pakistani counterparts, and held the strategic advantage.

At the end of August 1965, at the height of the Indo-Pakistani War, Indian troops had captured and occupied the Haji Pir pass and other important strategic territory in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Operation Gibraltar — Pakistan’s mujahideen-powered attempt to infiltrate and overthrow the government of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir — had failed. Indian forces were better-equipped and supplied than their Pakistani counterparts, and held the strategic advantage.Yet less than a month later India had accepted a UN-brokered ceasefire and handed most of the captured territory back to Pakistan.

The history of the 1965 war has an eerie familiarity about it. It first emerged more than four decades ago, but the same old song is still playing today.

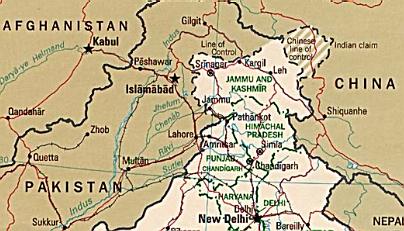

After a series of border skirmishes earlier in 1965, Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar at the beginning of August. In an attempt to overthrow the government of Jammu and Kashmir, native mujahideen from the Pakistani portion of Kashmir were recruited, trained, and led by Pakistan’s Special Forces. The plan was to infiltrate Jammu and Kashmir and induce discontented local Muslims on the Indian side to rise in rebellion. Together with their Pakistani saviors they would overturn the government in Srinagar, form a provisional government, and declare independence. The newly independent state would then call for help from other countries, including — no surprise — Pakistan. Islamabad would thus gain an enormous strategic advantage from a new puppet Islamic state on India’s northern frontier.

Such was the plan, but it didn’t work out as expected. The local Muslims on the Indian side of the Line of Control were indifferent to the idea of rebellion, and even went so far as to report the mujahideen to higher authorities. Pakistan had preserved plausible deniability — “Those aren’t our troops; they’re native mujahideen! They’ve got nothing to do with us! We never saw them before!” — but India was not fooled. Declassified State Department cables from the time show that the American intelligence services were well aware of Pakistan’s little game.

India responded to the provocation by sending its troops across the Line of Control, and drove Pakistan out of several important strongholds in Kashmir. The war escalated, spreading to other parts of the border between the two countries. A notable feature of the war was the largest tank battle since World War Two — so many American-supplied Pakistani tanks were destroyed or abandoned that the battlefield became know as Patton Nagar, or “Patton Town”.

As September wore on there was strong pressure from the United Nations for a ceasefire. Even the Soviet Union joined in — it had its own geostrategic reasons for wanting to rein in its Indian client. Finally, on September 22nd, the Security Council passed a unanimous ceasefire resolution, and the next day the war came to an end. The UN-brokered deal required India to give back most of the territory it had taken from Pakistan.

In hindsight, it is clear that India held the advantage over Pakistan. If the Indian army had pressed on, it could have dealt the enemy a complete and humiliating defeat; but, at the time, the generals at the front reported that Indian ammunition and equipment were nearly exhausted. This misinformation was part of the fog of war — later investigation by the Indian government showed that it was in fact Pakistan that was overextended.

India and Pakistan have gone to war over Palistan in 1947, 1965, and 1971, in addition to minor skirmishes and incidents that have occurred throughout the years since partition. Since nuclear stalemate imposed a moratorium on full-fledged war between the two countries, Pakistan has had to rely on its proxies to carry out aggression. It continues to train, encourage, and fund Islamic zealots to act as cross-border infiltrators, who are often trained in al-Qaeda’s terrorist camps in the lawless tribal areas or across the border in Afghanistan. During this entire time India has been under pressure, sometimes from factions within its own government, to make concessions to its foe in order to further the “peace process”.

Why does this pattern seem so familiar?

Exchange “Israel” for “India” and “Egypt-Jordan-Syria” for “Pakistan”, and you have the Palestinian problem in a nutshell:

- Mujahideen irregulars are employed as proxies to fight on behalf of an outside Islamic country.

- A militarily superior foe is pressured by the Great Powers to relinquish strategically important territory to a weaker enemy after attaining a clear military victory.

- A moral equivalence is established between the aggressor and the defender, so that “both sides” are continually urged into a “peace process” which notably disadvantages the defender, but fails to attain an actual peace.

- The conflict is never resolved. It continues year after year, decade after decade, with the implication that only more concessions by the original defender to the original aggressor can ever bring it to a close.

This infernal process was recently recapitulated in the war between Israel and Hizbullah in Lebanon, a war in which a non-uniformed proxy force of mujahideen engaged the Jewish state on behalf of its patrons in Syria and Iran. But in this case it seems the Prime Minister Ehud Olmert has internalized the whole perverse schema, pre-emptively declining to win the clear victory that Israel could have achieved so easily. Now, with the help of the UN, everything is being given back to Hizbullah, as personnel and arms once again flow into Lebanon from Syria.

For the four decades since the war, India has had to live with the consequences of the failure to defeat Pakistan in 1965. The issues have not gone away, and the Indian public remains mindful of what is at stake.

The latest contentious issue is the Siachen glacier, a strategic elevation in the north of Kashmir where India, Pakistan, and China come together. Over the last few months there have been persistent rumors — widespread enough to provoke official denial — that the Indian government is about to return Siachen to Pakistan as a conciliatory gesture.

Not everyone in India supports such appeasement. Consider this January 3rd editorial by Sarla Handoo in the Kashmir Herald, entitled “No Withdrawal from Siachen”:

A look, in retrospect, over India’s response to victories in wars with Pakistan, big or small, makes a dismal reading. It has been one of returning to the vanquished all that it could get hold of — after a huge sacrifice, of course.

[…]

India’s penchant to give away the booties has not been limited to the Simla agreement [the treaty signed after the Indo-Pakistani War in 1971]. In fact, it has been there at the end of every war with Pakistan. In 1965 Indian troops captured the strategically important position of Haji Pir in the Uri sector. This enabled the people of Uri, and of the Valley , to walk down to Poonch area of the state in four hours, which otherwise would mean a distance of 700 kilometers of hilly roads taking not less than three days by bus. For the people of Kashmir there could not have been a better victory against Pakistan. But alas, the post was returned to Pakistan in the wake of the Tashkent agreement between Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistan President General Ayub Khan. Indian troops were pulled back to their original positions. And this happened despite two important factors. One that Haji Pir falls within Pakistan occupied part of Jammu and Kashmir, which India claims as its own. And two, the victory of Haji Pir marked jubilation by the local residents who could taste a commodity like sugar for the first time in their lives, provided to them by the Jammu and Kashmir government.

In the Chhamb sector of Jammu region, the critical chicken-neck area was captured by the Indian troops several times during the course of wars, but was returned to Pakistan each time. Pakistan has now renamed the area, returned by India, as Iftikharabad, the victory land.

[…]

And now the air is thick with speculations that India is going to return the Siachen glacier to Pakistan and that the talks in this regard are at a very advanced stage. This is the point from where Indian troops are in a position to keep a vigil on the movement on Karakoram Highway between Pakistan and China and thereby provide security to the Ladakh region.

The road has been built after Pakistan handed over a portion of POK to China. It also gives a military advantage to Indian troops not only over Shyok and Nubra Valleys but also on the Pakistani positions located about 3000 feet below.

[…]

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is to visit Pakistan shortly. General Musharraf has already started to play his usual tune, saying that he hopes to achieve headway on what he calls the “simmering issues” of Kashmir and Siachen during Dr. Singh’s visit. For him terrorism is not a simmering issue and he is not bothered about it.

While attempts to normalise relations with Pakistan are welcome, India needs to be wary about Pakistan President’s moves. Accommodation beyond a point by India may not help. It has not during the last 58 years, at least. A ‘give-give’ attitude will only demoralise the Indian Army by concluding that it is no use to sacrifice lives for victory as the political executive will return the strategic points later on.

Even though India was a Soviet client in 1965, one regrets the fact that the Indian Army failed to continue all the way to Islamabad. Just think — no A.Q. Khan, no “Islamic bomb”, no Taliban, no technology for the DPRK. A different world.

What is wrong with us? Why can’t we see the pattern here?

By “us” I mean the United States, Europe, Israel, India, and all the other civilized countries confronting aggression from Islamic countries and their mujahid proxies.

The pattern is quite clear. Islamic dictatorships, unable to confront the infidels in state-to-state warfare, fund and train irregular non-state proxies to carry out their collective jihad obligations. Terror and attrition wear down the will of the infidel, until he finally makes conciliatory gestures. Conciliation is perceived as weakness by the enemy, encouraging more violence and greater demands.

This cycle can be repeated indefinitely, while the governments of the Islamic countries keep their hands clean and deny all responsibility, referring to the “legitimate grievances” of the oppressed Muslims as justification for all the atrocities.

For generation after generation our public servants have followed the same failed playbook. Most of us are safe from the consequences, at least for now.

But out there on the bloody borders of Islam, in Nigeria, Indonesia, Bosnia, Darfur, Serbia, Kashmir, Thailand, and Paris, the consequences are real enough. Real people are being hacked to death, beheaded, stoned, and burned alive due to the failure of our democratically elected governments to deal resolutely with the threat we will all eventually face.

When will we ever learn?

Resources on the conflicts in Kashmir:

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

Operation Gibraltar

The 1965 War: Lessons yet to be learnt (Rediff, 2005)

Lost opportunity in 1965 (India Daily, 2004)

Background on the 1947 war in Kashmir (Bharat Rakshak)

1 comment:

And what do you think of Obadiah Shoher's arguments against the peace process ( samsonblinded.org/blog/we-need-a-respite-from-peace.htm )?

Post a Comment